The flight from Elisenhof in Pomerania

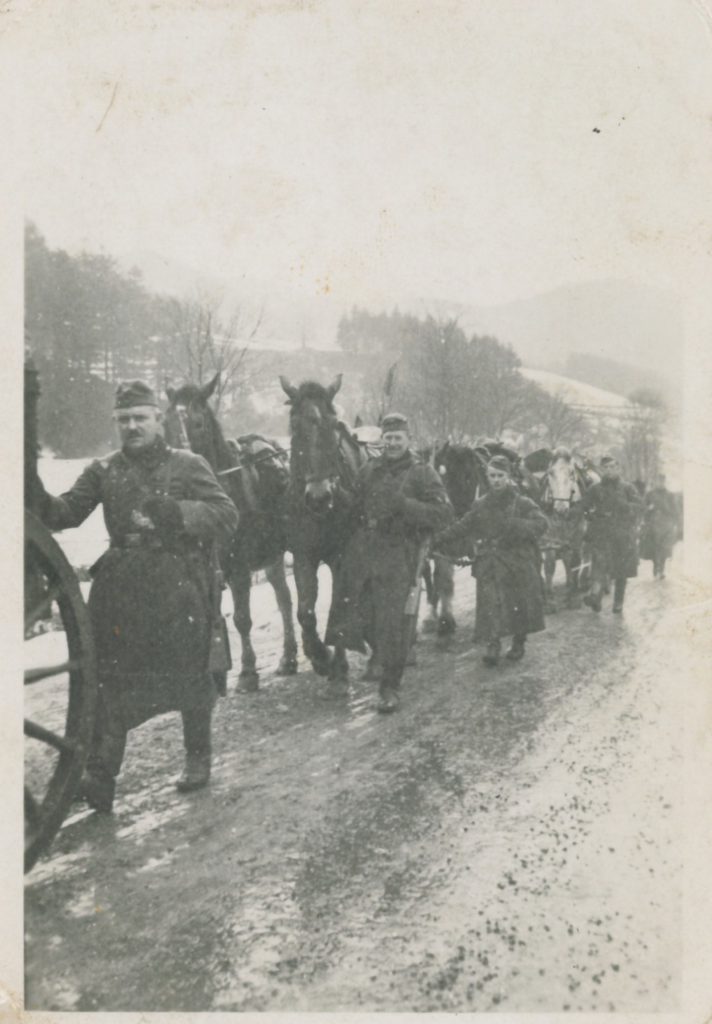

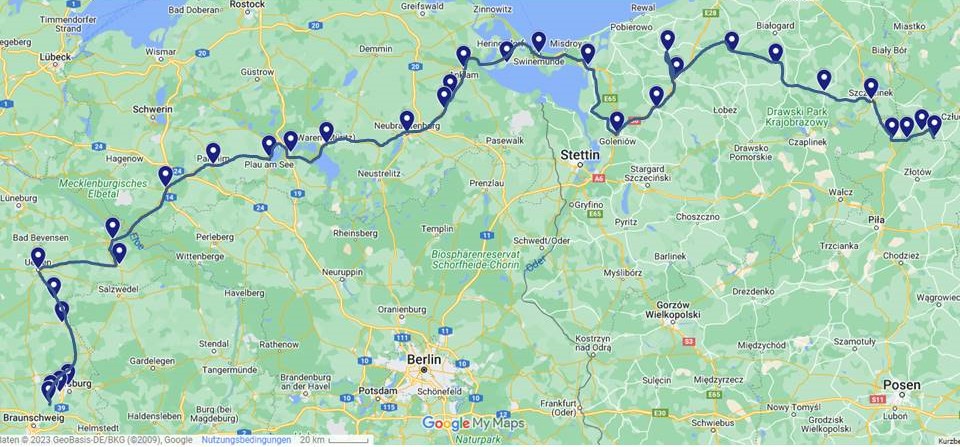

On January 29,1945, a community – the “Elisenhof-Trek“ – consisting of twelve families and two French prisoners of war, sets out from Pomerania to escape the approaching Red Army.

Already in December and increasingly in January, the first signs of a coming flight from Elisenhof appear. Streams of refugees from East Prussia pass by, filling the streets. Sometimes they stay overnight in Elisenhof. Even if the daily radio reports from the front are embellished with propagandistic victory messages, it soon becomes clear that the Russian front is drawing nearer.

On January 21, 1945, the authorities finally issue the so-called “Packing Order“ and order Elisenhof to prepare to flee. Three wagons made of wooden poles, tarpaulins and carpets are fitted with hoods. Since twelve families are to be accommodated in the covered wagons, only the most essential items can be brought along, most importantly food. In addition to the three wagons, a wagon fitted with ladder is loaded with hay and feed for the fourteen horses. Nobody knows where the flight will lead and how long it will take.

The flight from Elisenhof begins January 29, 1945. Waldemar Lück, then seven and a half years old, later remembers this day. In his flight memoir he writes about it:

January 29, 1945 was a freezing day. The thermometer dropped below minus 25

degrees. The thunder of guns and cannons was already threateningly close. In the

kitchen our dogs barked and whimpered. I lay in the cot next to my parents‘ double bed.

Later I fell asleep and woke up to knocking on the window pane. A voice shouted, ‘Be ready in an hour!’– Waldemar Lück in : “Flight from Elisenhof to Essenrode”

After all families are woken, they gather at and board the wagons in a previously determined order. Two French prisoners of war, the Bonuelle brothers, who had been sent to work on the estate, do not want to be “liberated” by the Russians under any circumstances and also join the trek. As wagon drivers, they play a major role in the success of the flight.

While the estate owner Theophil Boettcher is at war as an officer, his wife Gerta Boettcher takes over the leadership of the trek, supported by Waldemar Lück’s father, Emil. For orientation in the terrain, a Diercke atlas, found among the school supplies of Waldemar’s brother Gerhard, proves to be very helpful at first.

On a freezing cold night, the trek finally starts to move westward. Just in time, sixteen-year-old Kurt Nehring reaches the trek, which is already underway. Despite his young age, he had been conscripted for duty.

That night he [Kurt Nehring] had to transport military goods from Preußisch Friedland to Linde. Shortly before the destination, people said that Linde had already been occupied by the Russian army. He wanted to turn around, but on the narrow road he drove into the ditch and got stuck in the snow. He decided to take the eight-kilometre-long way home on foot. On the way he learned that the Elisenhof group was already on the move. So he ran the last stretch across the fields, always in fear of being late. Now he was considered a deserter and had to be kept hidden during the entire flight.

– Waldemar Lück in “Flight from Elisenhof to Essenrode”

One of the Elisenhof families decides not to flee. The Schwanz family stays mainly because one of the daughters in the neighboring village of Rosenfelde nursing her seriously ill husband. A momentous decision. When Russian soldiers arrive later, the seriously ill man and Mr Schwanz are immediately shot and the daughter is raped.

In the icy cold, starry night the trek goes forward, reaching Peterswalde still in the darkness of night. The journey continues northwards to Ratzebuhr. When the trek arrives there around noon, the pressures are showing on humans and animals. Some of the children are sick with fever and the horses are exhausted. Because of fear of looters the trek is always guarded. Finally, the next night, the trek continues to Neustettin. The advance of the Russian troops make it necessary to take evasive action in a northerly direction.

After the strains of the past days it was important to regain strength. Besides, the front had come to a standstill. So a few days’ break could be taken. One still hopes to return home.

– Waldemar Lück in “Flight from Elisenhof to Essenrode”

What nobody imagines is that the stay in Zwirnitz will last from 2 February to 1 March. In the meantime, other members of the trek fall seriously ill. There is no doctor to be found. At a pharmacy in the small town of Groß Rambin, eight kilometres away, an attempt to obtain medicine fails. There are only different kinds of tea and a small bag of dried blueberries. It’s still freezing cold and the snows starts again.

Newspapers no longer appear and no radio is available. In a nearby mill, which also produces electricity, it is finally possible to listen to a radio from time to time. When the Russian army reaches the Oder near Küstrin, the families are urged to leave Zwirnitz, but there’s a difficulty. The administrator of the Elisenhof estate has fallen ill with pneumonia and is in the hospital in Groß Rambin. Members of the Elisenhof community visit the dying administrator one last time in the hospital, and he dies the following day.

Once again, everything is stowed on the covered wagons and the flight continues March 1, 1945. Passing Bad Polizin, the refugees head for Stolzenberg. In the meantime, lice infest the clothes of some on the trek, increasing the risk of typhus for everyone. The next day the families continue toward Oder, but in Plathe they change their route and go further north. Soon, this is seen to be a mistake. The trek turns back to Plathe, then continues to Naugard. The next destination is Gollnow. The roads are overcrowded with horse-drawn carts and refugees. To the astonishment of the refugees, they must always move aside for military vehicles, which are obviously retreating to the west.

Towards evening all refugee wagons had to drive into a forest before Gollnow to keep the roads clear. They said there would be armored columns. I still remember that evening very well. The thunder of guns was clearly audible. Shells hissed over the trees. Many refugees had climbed down from the wagons and sought shelter beside them or under large trees. The German troops withdrew behind the Oder River. The Oder crossing at Gollnow was no longer passable.

– Waldemar Lück in “Flight from Elisenhof to Essenrode”

With the help of maps obtained from Wehrmacht soldiers, the trek makes its way north at night in secrecy and silence. Leading the way, Ms Hedwig Klabunde walks through the pitch-black night carrying a darkened lantern. They are silent and only communicate with signs. It is a ghostly procession through the dark forest, where not a word is spoken and only the muffled stamping of horses‘ hooves on the snowy ground can be heard. It goes on like this all night long until they arrive in a fishing village.

The proximity of the front creates unrest in the trek, so that the planned rest for the horses and the people is short. The trek starts moving toward Wollin. Since the area here is already equipped with many anti-tank barriers, the French wagon drivers need all their skill and ability to avoid the obstacles. The trek takes ten days to cover the twenty-seven-kilometre stretch across the island of Wollin to Swinemünde. The roads are so congested that on some days the trek only progress a few metres.

You had to spend the night on the wagons, which was difficult because of their narrowness and the cold. A big problem was nutrition. There was no food to be found anywhere. Not even bread. You had to live on the supplies you had brought with you. From time to time a fire was built at the roadside and hot tea was made from melted snow. The horses stood day and night in harness.

– Waldemar Lück in “Flight from Elisenhof to Essenrode”

The strains of the flight claim more victims. People fall ill as a result of the stress, the cold, the inadequate nutrition and the poor hygienic conditions, especially the already weakened infants. Two-year-old Christa Orthmann, for example, probably suffers from pneumonia. She dies March 8 in the arms of her mother, Hedwig, near the village of Misdroy.

It was not possible to dig a grave in the frozen ground. So the mother, accompanied by some girls, carried the body to the nearest village. This was the Baltic resort of Misdroy, several kilometres away. There the body was handed over to the authorities. It was not possible to wait for the funeral, because the trek had to continue. But a promise was made to bury the child with dignity.

– Waldemar Lück in “Flight from Elisenhof to Essenrode”

On the way again, the trek has to wait for days before Swinemünde for a crossing over the Swine. In order to cope with the flow of refugees, a pontoon bridge had been laid across the Swine, but it is defective and impassable. Now the only option is to take a ferry to get to the other bank. After another night of waiting, the trek crosses the next morning. The most dangerous part of the Oder crossing is done.

Thousands of refugees from the East – from East and West Prussia and Pomerania – are on the run during these March days, trying to continue their flight to the West through one of the last remaining open passages. The Elisenhof trek tries to avoid the congested roads and continues over the island of Usedom, past the Baltic seaside resorts of Ahlbeck, Heringsdorf and Bansin. The next evening and the following night the sky on the horizon is lit up by bright firelight, the consequences of the devastating air raid on Swinoujscie at noon on March 12 can be seen for miles around. The attack is aimed at the submarine fleet base. However, as it will turn out later, countless refugees are the ones who suffer. 4500 to 6000 people lose their lives. One day earlier, the Elisenhof trek would probably have been among the victims.

The trek continues its flight through the small town of Usedom and crosses the Peene River, the third estuary of the Oder. In Anklam, the trek visits one of the so-called refugee control centers for the first time. Here, the trek can get warm soup as well as information about the next destination. The refugee control centers in these last chaotic days of the war point to different destinations for the various treks. This is to avoid overloading individual roads and to disperse the refugees. From now on, the trek is forwarded from control center to control center.

Via Friedland, the route continues to Neubrandenburg. The relentless destruction of the war and the consequences for the Elisenhof community are apparent once again. Waldemar Lück describes the events of that day at Friedland:

Mrs Seringhaus had ten children. Her husband and the eldest son were in the military, the second eldest in the Reich Labor Service. She was very pregnant and had to flee with eight underage children. Near Friedland she went into labor. So her eleventh child was born on a refugee wagon. She needed medical attention. She stayed with her children in a village. She left all her belongings on the wagon, because she wanted to join them soon. This was a completely unrealistic idea, because at that time nobody knew where the trek would go. Later we learned that the family was taken to a refugee camp near Friedland. This camp was bombed. That is probably how the whole family died.

– Waldemar Lück in “Flight from Elisenhof to Essenrode”

Despite this tragedy, the trek must continue its flight.

The route leads via Neubrandenburg to Waren an der Müritz. As the days go by, the weather gradually gets warmer and the first tender green shoots of the meadows and forests are seen. Overnight stays are mostly on farms in a straw bed in barns or stables. However, the lack of horse feed is causing the animals to become more and more emaciated. Some of them do not survive these strains. It is always very sad when one of the animals, such a faithful companion during these difficult weeks, can no longer stand and has to be left behind, completely lifeless.

In these March days of 1945, the flight, which had begun on January 29, has now lasted several weeks and has claimed its victims. However, the flight is still not over. The trek leads through Mecklenburg and the cities of Malchow, Plau am See, Parchim and Ludwiglust.

In a forest behind Ludwiglust there is another air-raid alarm. The covered wagons hide as best they can under high trees. Everyone leaves the wagons and runs into the forest for safety. The fear of the low-flying planes is great. After that, another dangerous challenge awaits them: crossing the Elbe near Dömitz.

The fear was great of being shot at by the low-flying aircraft on the long bridge.

Therefore nobody was allowed to stay on the wagons except the drivers while crossing the bridge. My sister Magdalene got all the younger children together at the embankment. We waited until the wagons and the adults had crossed the bridge without incident. When everything was calm, we went over the bridge. A few days later the bridge was destroyed in an air raid.– Waldemar Lück in “Flight from Elisenhof to Essenrode”

The trek has been on the run for almost two months now. The trail continues from refugee control center to refugee control center in a southerly direction through the Wendland via Dannenberg, then Lüchow, to Uelzen. While the trail leads from Uelzen via Bodenteich to Wittingen, the trek learns that a temporary shelter can be found in the district of Gifhorn. In Wittingen, the trek is directed on. The village of Grassel is now named as the destination. The Elisenhof community stays together for the last time in a restaurant in Kästorf near the Volkswagen factory.

I can remember that we had to leave a weakened horse just before the finish. Via

Warmenau and Sandkamp, we came to Fallersleben.It was March 28, a beautiful spring day. Toward evening we passed through Essenrode, the last village before our destination, Grassel.

– Waldemar Lück in “Flight from Elisenhof to Essenrode”

The trek nears arrival at its designated destination, Grassel, but there’s a change of plan. The mayor and local group leader of Essenrode stop the trek. They tell the Elisenhof community that Grassel is already overcrowded. Their new destination is Essenrode.

On March 28, 1945, the flight from Elisenhof, which began on January 29, ends in Essenrode. The families from Elisenhof are distributed among the families of the village. The refugees’ reception by the families does not occur without protest, as the village has already taken in almost as many refugees as it has inhabitants. In the end, however, everyone gets a roof over their heads.

While the flight from Elisenhof is over, the war continues. Even the older men who arrived with the Elisenhof trek are drafted into the Volkssturm (At the end of the war, the Nazis mobilised children and old men in the so-called Volkssturm for defence.) with the idea to defend the military airfield in Wesendorf. They are housed in barracks and the following night the airfield is bombed by aircraft and completely destroyed. As the American troops approach, the men make their way back to Essenrode on foot in the dark of night, which is repeatedly illuminated by exploding bombs.

Waldemar Lück will later describe the last day of the war for him and the experiences of the “old men” of Elisenhof in this way:

Since they were all conscripted for duty, they set off again for Wesendorf on Monday. There they met an officer. ‘What are you doing here?’ he said. ‘There’s nothing left to protect here. The Americans are already at the door. Turn around and go home.’

From Allenbüttel, they walked along field paths and across meadows. From the valley they saw American tanks drawn up in front of the village. Always looking for cover, in order not to end up in captivity, they made for the village and arrived there completely exhausted in the morning.

On this day the Americans came to the village. For us the war was over.

– Waldemar Lück in “Flight from Elisenhof to Essenrode”

On April 11, 1945, the war ends with the arrival of American soldiers in Essenrode.

One month later, the Second World War in Europe comes to an end with the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht. The criminal war of aggression by Nazi Germany and the atrocities committed in the name of National Socialist ideology come to an end.

The consequences of the war and its continuing effects will accompany many people throughout their lives – including those from the Elisenhof community. Some of it is processed, some continues to have an effect, even upon later generations.

Normal 0 21 false false false EN-US X-NONE X-NONE /* Style Definitions */ table.MsoNormalTable {mso-style-name:"Normale Tabelle"; mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0; mso-tstyle-colband-size:0; mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-parent:""; mso-padding-alt:0cm 5.4pt 0cm 5.4pt; mso-para-margin:0cm; mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri","sans-serif"; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-ansi-language:EN-US; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} Thanks to

We would like to thank Waldemar Lück († 31.03.2025) and all the others who have contributed to making the experiences of the Elisenhof community tangible for us as later generations. It gives us the opportunity to listen sincerely to them and what they have to say to us, and to share what they have experienced with each other – for a better future.