Displacement from Silesia

Dorchen Remus is born Dorothea Gebauer on July 8, 1935, her parents´ second child in the small Silesian town of Tscherbeney in the county of Glatz. Soon she is called Dorchen by all.

When Dorchen is a year and a half old her mother dies. After her mother`s death she and her brother Siegfried are separated from their father and go to live with their grandparents. When the father marries a second time, in 1941, Dorothea returns to the family for school enrolment, which in the meantime has moved to a factory building in Sakisch in Silesia. Father and mother work in the Christian Dierig weaving mill in Sakisch-Gellenau. Shortly afterwards, the father is drafted into the army.

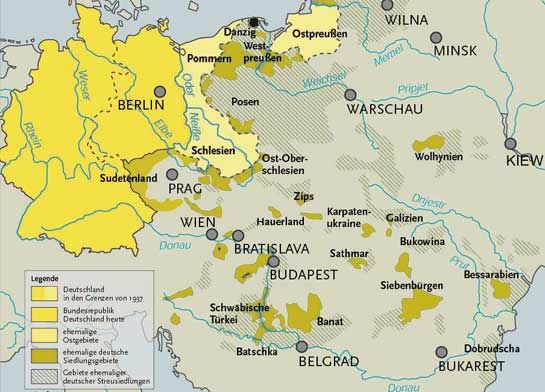

Dorchen remains in Sakisch for the time being after the end of the war. Like thousands of other Germans, she is expelled from Silesia soon afterwards. An expulsion is a result of the National Socialists´ tyranny.

“During the time of National Socialism, Tscherbeney was renamed Grenzeck in 1937. As a consequence of the Second World War, in 1945, Tscherbeney / Grenzeck fell to Poland, as did almost all of Silesia, and was renamed first Czerwone and later Czermna. Most of the German population was displaced. Even before that, numerous inhabitants had fled across the nearby border into Czechoslovakia. The new settlers were themselves partly displaced from eastern Poland. In the 1950s, Czermna was incorporated into Kudowa-Zdrój.” Source: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Czermna

Until the end of the war, Silesia and the Sudetenland were comparatively quiet hinterlands and evacuation areas for the population of the cities and industrial regions located to the west, which had been heavily affected by the bombing.

In January 1945 people also began to flee from the Red Army in Silesia, some to Saxony and Thuringia, others over the Krkonose Mountains into the Sudetenland.

“From 1944 until the end of the war, up to six million Germans were evacuated from areas east of the Oder-Neisse line or had to flee. Many of them returned when the war ceased. Once back home, they experienced what had already become bitter everyday life for those left behind and for those in areas overrun by the army from the front: looting and mistreatment, arbitrary shootings – and the women mass-raped by soldiers and officers of the Red Army. People hoped that these excesses, fed by a mixture of the rush of victory and the need for retribution, would be temporary and believed that the situation would return to normal after the end of the war.

Poland, which had been divided by Hitler and Stalin in 1939 for the fourth time in its history by Germans and Russians and after the Second World War, did not recover much of its pre-war territory in the East, but was compensated with Silesia, Pomerania and the southern part of East Prussia. It wanted to empty these areas of their German inhabitants as quickly as possible in order to prevent future attempts to annex Germany and to support its thesis that these were in any case reclaimed areas of Unpolish origin. At the same time, the people who were expelled from the part of the country that remained with the Soviet Union were to be accommodated there.” Source: https://www.lwl.org/aufbau-west/LWL/Kultur/Aufbau_West/flucht/flucht_vertreibung/ablauf/index.html

End of the war in Sakisch

While Dorchen’s father has not yet returned from the war, Dorchen remains in a factory apartment of the weaving mill with her “second” mother and her sister Lenchen, born in 1942, after the war ends. Three days before the Russian army invades Sakisch, Dorchen’s mother gives birth to twins Evi and Günther. The end of the war becomes clear to the nine-year-old Dorchen when she sees Russian soldiers driving through the streets of Sakisch on their way to the hospital. Dorchen and her family have no bad experiences with Russian soldiers in Sakisch. One of the apartments in the factory building where she lives with her family has to be cleared for the Russian command. Later, Polish soldiers live in the apartment as subtenants.Today she says:

This spared us from looting and assault. The Russians were good to us children. They made toys for us and sang songs with us.

– Dorothea Remus in an interview as a contemporary witness, 2019

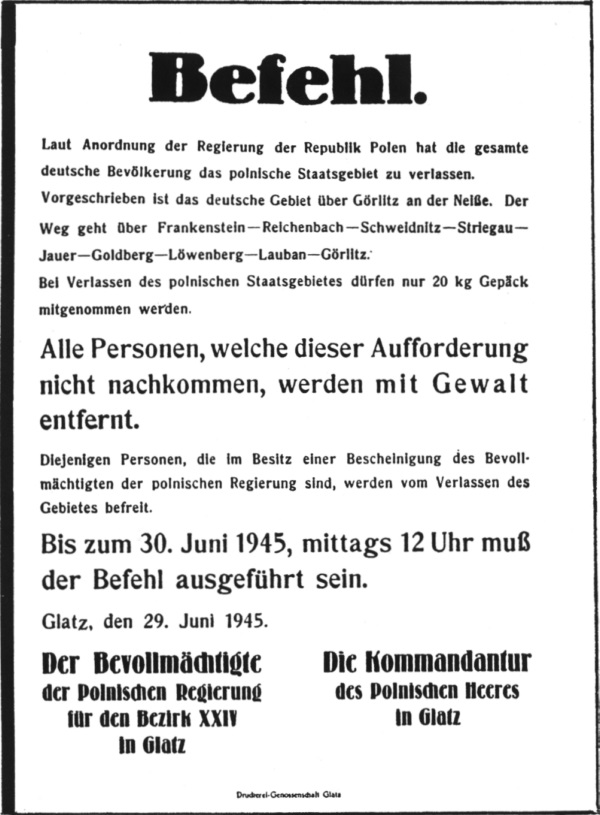

Displacement

Dorchen remains in Sakisch with her mother and siblings until 22 March 1946. Then she too meets the fate of expulsion. On that day they, like all the other Germans who remained there, are ordered to leave Silesia, which now belongs to Poland. The apartment must be vacated immediately. They spend the night at the tax office in Glatz. The next morning they go to the train station. From there the journey continues in cattle cars into the unknown.

The train, which is heading west, makes frequent stops along the way. The German Red Cross tries to distribute food as best it can. In Kohlfurt all train passengers are deloused.

“The average stay of the trains in Kohlfurt/Kalawsk should not take longer than three hours. The displaced persons had to leave the carriages and were counted on the platform in rows of two by the British soldiers whose presence was benevolently recorded. Also on the platform, they were then subjected to a procedure which will have remained in the unpleasant memory of all concerned: delousing. Each of them was struck with a vacuum cleaner-like device in five blows, first in the hair, then under the shirt, with a grey powder, DDT, on the skin at the front and back. At that time people were not yet sensitized to the fact that DDT not only effectively combats vermin such as lice, but is also extremely harmful to humans and nature.” Source: MANFRED WOLF, Operation Swallow; Der Weg von Schlesien nach Westfalen im Jahre 1946; Source: Westfälische Zeitschrift 34, 1999 / Internet-Portal “Westfälische Geschichte” URL: http://www.westfaelische-zeitschrift.lwl.org

From Kohlfurt the train continues its journey and finally arrives in Helmstedt Mariental. Part of the former military airbase Mariental serves as a transit camp for displaced persons from November 1945 to April 1947. For about 750,000 people, most of them from Silesia, Mariental is the stopover on a train journey into the unknown. From here they are sent to villages and towns.

Arrival in Wendhausen

After their arrival, the people from Glatz stay overnight in the Mariental transit camp before continuing on to Lehre the next day. In Lehre, Dorchen and her family are first accommodated in barracks on the Muna site (an ammunition depot) before being distributed to the surrounding villages. The community of people from the factory buildings of the weaving mill in Sakisch finally end up together in Wendhausen. There the five family members of the Gebauer family are accommodated in two small rooms on a farm. Dorchen’s father is released from the military hospital in Tirschenreuth some time later and finds his way back to his family. He immediately finds a new job with Voigtländer in Braunschweig.

A few years later, as a young woman, Dorchen falls in love with Rudi Remus, who fled from Pomerania to Essenrode in spring 1945. They marry, live together in Wendhausen and in 1958 their son Dieter is born. In the 1970s they will move to Essenrode, where they build a privat home for themselves.